How far would you go to get The Shot? I’ve recently been reading up on the seminal British magazine, Picture Post (1938-1957) which, at its height, had around five million readers. Considered to represent the golden age of photojournalism, I was somewhat alarmed by multiple accounts of its lauded photographers constructing images to tell the story.

Most of it seemed on the right side of the moral line. When Thurston Hopkins photographed in Liverpool’s slums, he encountered an empty child’s bed covered in newspaper to keep rain off the bedclothes. He waited until the child returned from school and then asked for her to be put to bed, just as she would be on any night, then took the photo. It’s constructed but faithful to the truth.

The two women in Kurt Hutton’s famously saucy photograph on the caterpillar ride in Southend as one skirt is blown up by the wind, were models sourced from a film agency (the magazine’s editing department lengthened the skirt to cover her panties). Legendary documentarian, Bill Brandt, is said to have used members of his own family dressed as east end gang members in his photographs - to me that seems to be more of a leap over the moral line.

The construction of photographs wasn’t restricted to when photojournalists wore hats, jackets and ties and smoked a pipe. In 2010, The Natural History Museum, Wildlife Photographer of the Year winner, José Luis Rodriguez, was stripped of his £10,000 prize after judges found that he was suspected of hiring a tame Iberian wolf in order to stage his winning image (entries must not deceive the viewer or attempt to misrepresent the reality of nature).

In 2017, a winning entry by Marcio Cabral was similarly disqualified for featuring an anteater after it was decided it was ‘highly likely’ a taxidermy specimen. In 2012, photographer David Byrne had his £10,000 prize revoked as overall winner of the Landscape Photographer of the Year competition after judges ruled he had excessively employed Photoshop before submitting his image, Lindisfarne Boats.

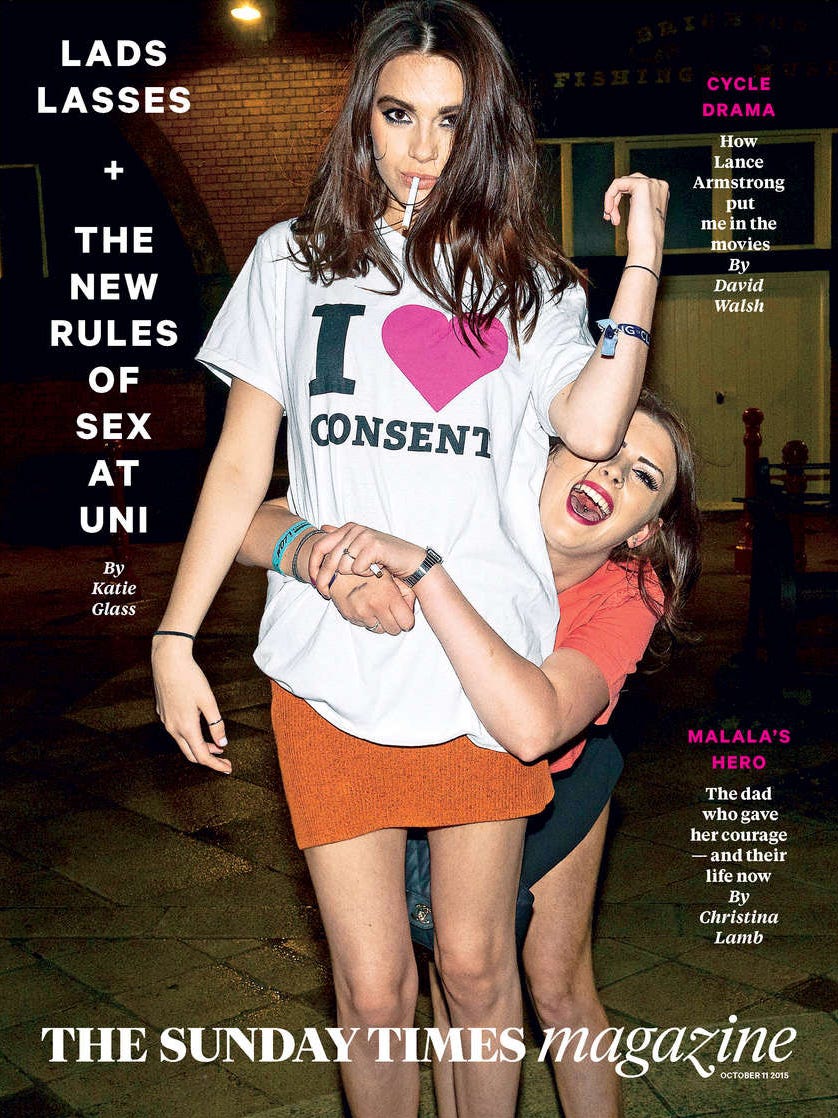

I’m well aware of having to get the shot. In September 2015, I was commissioned by The Sunday Times magazine (STM) to report on the new rules of sex at university. Sexual harassment and laddish behaviour on campus had reached epidemic levels and the authorities were clamping down.

The University of Sussex had launched an ‘I Heart Consent’ campaign, that aimed to tackle myths, misunderstandings and problematic perspectives about rape, sexual consent and sexual harassment and they were looking to educate Sussex students on these issues. They had badges and a T-shirt, which I purchased from the campus shop so that I could take a few still life pictures on Brighton beach. The images looked ok but it would have been better if someone had been wearing the goods. I stuffed it in my camera bag in preparation for the night ahead.

The journalist I was working with had acquired tickets to a freshers’ party on Brighton Pier. It was to be a covert introduction and I took along my unassuming looking Olympus EM5 Mark II (one of a limited edition of 6,000) to do the job. Not perhaps looking quite as inconspicuous as I’d hoped, I bounced along with freshers who were finding alternative ways to achieve light-headedness on a trampoline, riding the TURBO roller coaster, dodgems and being tossed off a mechanical bucking-bronco. I didn’t see anyone wearing the consent T-shirt.

Around 1pm, on our way to down shots at another freshers’ party at the nearby Wah Kiki club, we bumped into fashion student Sophie on a night out with her mates and we got chatting to her about the I Heart Consent movement. Sophie was understanding and in favour of it, so I asked if she’d be ok wearing the campaign T-shirt for a few photographs. I felt it was the right side of the moral line to get the shot I needed and fired off around 11 frames.

Afterwards, she was interviewed by the journalist. On October 11, the photograph of Sophie ran on the STM cover, a cigarette dangling from her mouth, her friend clasped around her waist (the cover went on to win an industry award). Then I received a phone call from the picture desk: Sophie’s family had been in touch to say she had no recollection of being photographed and could she be put in touch with the photographer. Over the next few weeks we corresponded, followed each other on social media, advised on how her sister might break into modelling and I sent copies of the cover photograph.

Sophie wasn’t the first person to reach out after seeing themselves in print and she wasn’t to be the last. After another STM article published in July 2017 about the English Summer Season and the new rules of high society, I was offered an exhibition at WEX photographic in London. Following some publicity about the show being featured on London Live, I received the following email: Hello, I am one of the people featured in your Summer Racing exhibition. I was hoping to be able to get a print? Can I come along to the exhibition too? Cheers John.

The image shows six-foot-six John, who works as news editor/ deputy editor for a weekly tabloid, splayed out on the grass at Royal Ascot, pint clasped in hand. John turned out to be excellent company and the exhibition print I gave him now hangs proudly on his wall. Apart from the mother who threatened to report me to the press complaints commission after a photograph of her daughter grinding on the legs of a man at a school disco-themed night out was published across two pages in the STM, most of the time people have recognised themselves, or someone close to them in my photographs, it's turned out to be a positive experience.

What will be the outcome next time you go out to get The Shot?

Really liked this one, Peter. The image of Sophie is top class- the background on how you managed it is even better. Cheers.