The Informer

A book of iconic photographs taken by Mike Abrahams delivers 30 years of British history.

A resounding applause fills The Four Corners Gallery and arts centre dedicated to independent photography and film-making. Fifty or so people have travelled from across the country to east London to see and hear photographer Mike Abrahams speak about his new book, This Was Then (Bluecoat Press 2024). Abrahams doesn’t take questions and politely directs people towards the complimentary bar. Surveying the dispersing crowd I spot renowned picture editors, archivists, publishers, editors and photographers. They are of an age and of a time. This Was Then is a collection of Abrahams’ photography from 1973 to 2001, through Prime Ministers Heath, Wilson, Callaghan, Thatcher, Major to Blair. It was his time and his visual contribution to this era of British history.

Born in South Africa, Abrahams left aged two and grew up in Liverpool, UK, where he began taking pictures as a teenager as a way to explore his surroundings. ‘In 1971, as a 19-year-old, I worked on ambulances, taking the elderly and disabled to day centres. Entering some of the last occupied houses in condemned streets awaiting demolition was shocking and it was to some of these streets that I returned later with my camera,’ he writes in the introduction to This Was Then.

During the afternoon I spent listening and chatting to Abrahams, it’s evident he’s moulded by the bomb-damaged, slum-ridden, impoverished environment of his youth. Driven by an unwavering curiosity, decades of wandering British streets to see what’s around the corner and behind doors of those living day to day in marginalised societies has followed – Blackburn, Bradford, Barrow-in-Furness, London, Liverpool and Glasgow.

Northern Ireland features prominently in the book. The images are political but more often show the moments in-between, the disparity between what is a war zone and daily life. A repeated phrase by Abrahams about his method is, ‘I was not interested in the fact that people threw stones, only in why they threw them. I want viewers to ask the same questions.’ Two kids chat on their bicycles, a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) logo sprayed on the wall behind, two armed soldiers have taken up covered positions; A man leans on his walking stick watching two soldiers fix a corrugated iron barricade across a street; A child looks out from a caravan, hands pressed together as if in prayer, in the background, a fortified British border post.

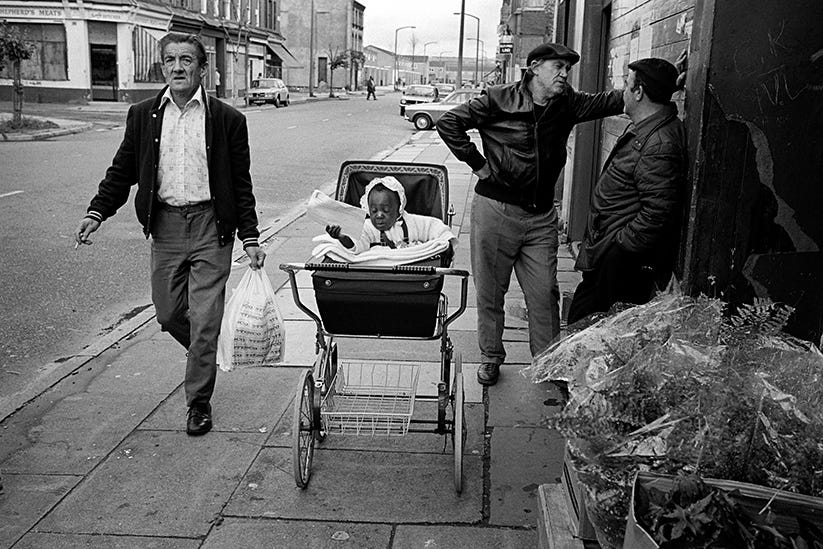

‘For me street photography is about seeing the information in a picture and telling a story. It’s not about shapes, colour and light. That’s some people’s approach to street photography and that’s fine. For me it’s about information,’ he says. Abrahams technique – working close using a Leica with a 35mm or 28mm lens with an external viewfinder clipped on top – packs in the information, the framing always right to the edge.

In 1987 he photographed the delayed funeral of IRA member Laurence Marley, one of the masterminds behind the 1983 mass escape of republican prisoners from the Maze Prison, where Marley was imprisoned at the time (although he didn’t participate in the break-out). Marley was fatally shot on 2 April 1987 by an Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) unit that drove to his home in Ardoyne. It was a potentially explosive situation but Abrahams was prepared. ‘I knew them all. I stayed in Ardoyne quite a long time. I think that was very important working in Northern Island at that time. Whichever community you were working with, somebody along the way had to recognise you were okay. Once that box had been ticked, it was okay.’

‘Sometimes cowering behind a wall when things go shitty is a good place to be,’ he explains candidly. He’s referring to an extraordinary photograph of mourners racing for and taking cover during the populous funeral of three IRA members killed in Gibraltar. Ulster Defence Association (UDA) member, Michael Stone, attacked with hand grenades and pistols after he had learned there would be no police or armed IRA members at the cemetery.

There are several images in the book that connect deeply through eye contact. ‘It was 1987. Someone was moving house. A truck was being loaded up with belongings. This young lad was helping. There was something about his look I found compelling, vulnerable, he was slight, you could say he was a little weedy if you were being a bit cruel, there was something about his drooping eye that was disturbing. He leant his arm across a piece of furniture that mirrored the mountain behind. We caught each other’s eye and I said, “do you mind if I make a picture?” You take the picture and move on.’

Six years later at 13:06 on 23 October, a bomb detonated at Frizzell’s fish shop on Shankill Road, killing nine and injuring over 50. On the news was posted a picture of the two IRA bombers, Sean Kelly and Thomas Begley. Abrahams recognised that drooping eye. ‘If you’re going to call something a portrait, this is a portrait. I know it’s an old cliché but I have very strong feelings that you’ve got to get inside someone. It was a collaboration in that very brief moment where he gave something quite strong to me and I think I gave him something back. Then we said our farewells and I was gone.’ The photograph of Begley, who was also killed in the bombing, was briefly considered as the book cover but dismissed as too problematic.

What is special and smart about Abraham’s photographs is they are often generalised pictures of race, conflict or poverty. He shoots beyond the news report, producing pictures that can be repeatedly used in numerous ways in news outlets to illustrate articles in a way that draws the reader in. The cover of the book is a carefully observed photograph of a teenage boy, a row of tenement houses behind him. It’s tense, the eye contact, again direct. ‘This young man was photographed in Cranhill, an estate in Glasgow where there was an epidemic of heroin abuse. I went there to do a story on Mothers Against Drugs. It’s an interesting picture because it ticks all the boxes graphically, it’s a bit ambiguous, and in some ways I like ambiguity because it’s not really telling you what to think. I don’t know if he was a drug user, in a way I don’t care about that; for me it’s an issue of what is the environment in which a major drug issue is existing.’

What is also astute about Abrahams is his recognition to be proactive in the circulation of his photography. In 1981 he co-founded Network, an independent cooperatively-owned picture agency along with Steve Benbow, Chris Davies, Mike Goldwater, Barry Lewis, Judah Passow, Laurie Sparham and John Sturrock. He says, ‘Our mission was to support and encourage making good documentary photography and enable that to be distribute widely and for us to be able to make a living.’

Several veterans of those times in the gallery nod along. He continues, ‘We supported each other emotionally, creatively and financially. That was a golden time of British photography. I like to think there was a real bond between us, collaborative not competitive, and we were able to encourage help and enable us all to do the work we really cared about and produce significant bodies of work across the world.’ Network eventually closed in 2005.

The presentation of This Was Then is simple and traditional, a series of pictures without a break, an onslaught of juxtapositions, one next to the other. ‘That’s something I felt quite strongly about. Because it’s historic and not narrative and not linear, I like the way this picture relates to that picture. It says something else. There’s another language going on. That’s what I enjoy. There are pages where the picture on the left page is the same situation or scene as the right-hand page. It’s to do with how they speak to each other.’

The captions are location and date, down to Abrahams not making extensive notes at the time. ‘I think if I had kept very rigorous diaries, recordings and interviews with people with their words, that would’ve been something quite different. I didn’t have the resources, I didn’t have that information.’ His consistent, high-quality black & white style uniforms the scenes and subjects in the book.

One of Abrahams’ most important personal pictures was taken on assignment for The Observer in 1981. He explains; ‘I was sent to do a story on Birkenhead’s Ford Estate. A 12-year-old girl had won a junior poetry prize competition. She’d written poems about life on the estate which I never saw. My job was just to go, hang out and take pictures of the estate to accompany what she was doing. I got there, it was a day shoot. I found these bunch of about 14, 15 young ones lounging on the grass. It was a sunny afternoon, they were drinking a few cans, smoking a bit of weed, nothing unusual. I hung out with them all day. It was a nice day, we just did stuff they were doing.’ Six months later heroin ravaged the estate. ‘Twenty-three years later I revisited with John, one of the lads on that grassy mound. We met up with another four survivors of that time and events of that weekend were recounted in great detail. Of those young people, to my shock, only five remained alive.’

It’s one fascinating example among many how a picture changes its meaning with knowledge and history. Abrahams has travelled the world on assignment but it’s this work on Britain that deeply resonates. He may not have kept extensive notes and interviews but his archive is a trove of information. ‘As a photographer it’s a privilege to have met people and been to places I would otherwise not have gone and met thousands. There were situations and individuals that remain in your memory but a lot of that world gets lost. The most humbling thing was this lad remembered the day a man from The Observer came and paid attention to him and that was very humbling and that’s all I’ve got to say.’

A selection from This Was Then by Abrahams will be exhibited at Photo North Festival #6 at the Carriageworks Theatre, Leeds, UK from 11-13 April 2025

Thank you for introducing Mike Abrahams to me. I instantly ordered that book. The effort you have put in that post is truly valuable. I appreciate it a lot.

Excellent read! Thank you for sharing!